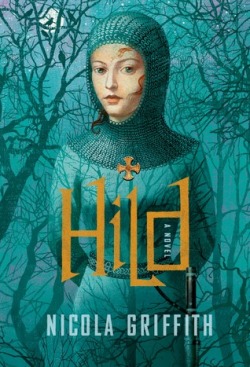

Many other reviews of Nicola Griffith’s stunning new novel Hild will be written by people who have a much deeper understanding of its historical period, its main character, and the author’s previous works. Sadly, I am a blank slate when it comes to all three: prior to reading Hild, I had very little knowledge of Seventh Century England or St. Hilda of Whitby, and (to my great shame) Hild is the first novel I’ve read by Griffith.

Many other reviews of Nicola Griffith’s stunning new novel Hild will be written by people who have a much deeper understanding of its historical period, its main character, and the author’s previous works. Sadly, I am a blank slate when it comes to all three: prior to reading Hild, I had very little knowledge of Seventh Century England or St. Hilda of Whitby, and (to my great shame) Hild is the first novel I’ve read by Griffith.

I’m starting this review with that information because I believe many other genre readers will be in the same position and may, like me, be a bit intimidated by the idea of a historical novel in an unfamiliar setting about a character they only vaguely know.

If that describes you and you’re on the fence, dear reader, I am here to tell you: don’t hesitate. Read this book. It is wonderful and your life will be the richer for it.

So, with that out of the way: Hild is the story of Hilda of Whitby: a central figure in the conversion of England to Christianity, an adviser to kings, and often described as the most powerful woman in Seventh Century England. Most of what we know about her life comes from the Venerable Bede’ Ecclesiastical History of the English. That’s about the sum total of what I knew when I started reading Hild, and I think that’s all you need to enjoy the novel. Go read the Wikipedia article if you feel like you have to.

(That’s not to say that people who have the relevant historical knowledge won’t get more out of this novel or may have an easier time keeping some of the era’s rulers separate. I’m just saying a lack of such knowledge shouldn’t dissuade you from reading this book.)

In Hild’s time, Britain is a fractured realm of minor kingdoms. There’s a constant power struggle between kings for territory and trade. Christianity is trying to establish a foothold in a country that still worships the old gods. The Roman Empire fell a long time ago; the Norman Invasion is centuries away. Britain in the early Middle Ages is a brutal, almost unrecognizable place, yet one that’s central to the evolution of the country (or rather, countries) it would become.

Hild is the niece of Edwin of Northumbria, the overking who is trying to expand his territory through whatever means necessary. Her father, king Hereric, was poisoned when she was still an infant. Her mother, Breguswith, is doing all she can to create a space in the world for herself and young Hild, at a time when being the female relative of a vanquished ruler is not exactly a great starting position.

Hild turns out to be a uniquely gifted child, mainly because of her amazing powers of observation and her ability to extract knowledge from patterns and facts. She has a way of looking at the world and making predictions that feels like magic to the people around her. Her uncanny appearance and intensity reinforces that otherworldly impression. Hild becomes Edwin’s seer and one of the most mysterious figures in his court.

Hild-the-novel is mostly told from Hild-the-character’s perspective, which creates an astonishing level of ambiguity. As readers, we know that Hild’s incisive intellect and strong powers of observation are nothing supernatural: she sees patterns where others see chaos, has the ability to reach conclusions based on those patterns, and is smart enough to know when she should or shouldn’t pronounce those conclusions.

But for the people around her, even the most powerful ones, it feels like magic. Edwin is happy to take advantage of this to advance his own goals. Others are terrified by the strange girl with the power to see the future. The Christian bishop vying for the king’s ear and the people’s souls sees her as competition. Hild treads a delicate line.

Hild is the central focus of the novel, but Nicola Griffith surrounds her with supporting characters who rival lesser novels’ protagonists in complexity. She also creates a setting that is obviously not just a labor of love but also the result of an astonishing amount of research, yet never has the “let me explain how the world was in this era” problem many historical novels suffer from. (If you’re interested in finding out more, check out the blog Nicole Griffith maintained while writing and doing research for Hild.)

There are so many aspects to this novel that it’s practically impossible to touch on all of them in a review, but here’s just one more that struck me early on and fascinated me to such an extent that I ended up contacting the author about it: Nicola Griffith’s prose in this novel isn’t just gorgeous (it is), but also remarkable in that it seems to avoid many of the Latin cognates that are so common in modern English. While the novel obviously isn’t written in the actual Old English of the era, this lack of Latin-derived polysyllabics gives the book an odd, uniquely appropriate atmosphere.

Even more impressive: the language seems to evolve as Hild gets older and could reasonably have been exposed to new vocabulary. At one point, the word “collect” or “collection” jumped out at me (rather than, say, “gather”) because it seemed incongruous, so I asked the author via email:

I have a question about your use of language in Hild. It almost feels as if you were trying to avoid Latin-derived words or cognates, to the point where it surprised me when you used e.g. something like “collection” instead of “gathering”. (The names are another obvious one, with the exception of the Christian priests and bishops.) Were you purposely doing this? It really emphasizes the pre-1066 early Middle Ages atmosphere of the novel, and it’s so subtle that I barely noticed it until one of those few cognates jumped out at me.

Nicola Griffith responded:

I did try avoid Latin polysyllabics, yes. As much as possible I stuck with words that might plausibly have been around in Hild’s time. I did cheat here and there when I thought the prose would have been better for it. And, of course, I let the Christian priests use any words they wanted in their dialogue.

I don’t remember ‘collection’ but I’m hoping (!) it happens late in the book when Hild might have been reading some Latin communication or other (perhaps from Fursey). But, er, it’s possible that it just slipped through my language net.

(She also suggested a few articles from her blog that focus on this subject in more detail: The never-ending mystery of English and Slavery, language, and cultural annihilation. The word cloud here is also revealing in that respect.)

But again, this is just one aspect of a novel that begs to be mined for further analysis. Character relations. The evolution of religion. The economics of the novel. The role of gender. The very spot this novel occupies at a confluence of genres and subgenres. All of these and more are potential, rich veins for discussion and analysis.

But, in the end, all I can do is urge you to check out Hild. This is a journey of a novel. I was lost to the world reading it. If you’re only going to read one historical novel this year, make it this one. If you weren’t planning on reading a historical novel, read it anyway. Buy it this weekend: it will be, after all, the Feast Day of St. Hilda.

(One more thing! A fun fact I stumbled across during the many happy research click-fests that this novel led me to: Hild carries around a “snakestone” – what we would now call an ammonite. See also: Nicola Griffith’s debut novel Ammonite. And, even better: the ammonite genus Hildoceras takes its scientific name from St. Hilda. This kind of thing makes me ridiculously happy.)

Pingback: You can pick it up if you come in with ID. | Magpie & Whale

As always, your blog is the first to introduce me to new books that absolutely must be read RIGHT NOW. I am ever thankful, even if my bookshelves complain.

Love to hear that! This is definitely one to read – it’s extraordinary.

Hello

I’m wondering the recommend age for this book? Is my 13 year old ( girl) too young?

Thanks very much.

I’m a bad person to ask this because my parents let me read almost anything from an early age, but as much as I love this book and recommend it to anyone, I’d say it’s not aimed specifically at a young adult/middle school audience.

Pingback: 2013: The Year In Review | Far Beyond Reality