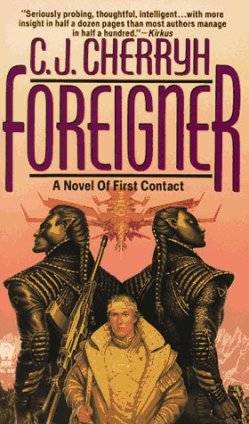

Foreigner is the opening volume of what has turned out to be C.J. Cherryh’s longest series. When I first read it, some time in the early 2000’s when the series only consisted of six books, I had no idea that this story would turn out to be five arcs of three books each, with the fifteenth novel due out in 2014 and the first book of a sixth arc reportedly in the works. That’s fifteen books going on sixteen, in case anyone else is in the mood for a nice meaty SF series.

Foreigner is the opening volume of what has turned out to be C.J. Cherryh’s longest series. When I first read it, some time in the early 2000’s when the series only consisted of six books, I had no idea that this story would turn out to be five arcs of three books each, with the fifteenth novel due out in 2014 and the first book of a sixth arc reportedly in the works. That’s fifteen books going on sixteen, in case anyone else is in the mood for a nice meaty SF series.

My history with this series is a bit confused. I’ve read about three dozen of Cherryh’s novels; the only authors I’ve read more individual works by are Pratchett and, maybe, L.E. Modesitt Jr. For some reason, it’s been a few years since I picked up one of Cherryh’s books. I read the first six books in the Foreigner universe practically back to back, then for some reason completely lost track of the series for over a decade.

When I decided to indulge and pick up one of her older books (“indulge” because there were about twenty new books I should have been reading instead), I was tempted to go for book seven of the Foreigner series, but quickly realized that I just didn’t remember enough detail from the earlier books. So I decided to treat myself to a reread of those first six books. And that, dear reader, is the reason you’re seeing a review of a book that’s almost twenty years old on this blog today.

Foreigner is essentially a first contact story about aliens landing on a planet and having to learn to deal with its inhabitants. The big twist is that we’re the aliens. A human colony ship got lost in space after a bad hyperspace jump. The first two sections of Foreigner fast-forward through their journey, their arrival in the new system, the horrific challenges they face as they realize there is no way home. These two sections only account for about one seventh of the novel (about 60 of my paperback’s 420 or so pages) and should probably be considered something like a prologue to the entire series, because it’s only afterwards that the real story gets started.

As the third section of Foreigner begins, we meet Bren, the human paidhi who lives with the alien atevi. A combination of translator, observer, and diplomat, the paidhi position is an essential link between the two cultures and the only human allowed to leave the island where humanity has settled. About two hundred years have passed since the human/atevi war that created this delicate balance.

This third section starts, quite literally, with a bang, as Bren is forced to defend himself against an unknown assassin, using a gun he just received as a gift from Tabini, an important atevi leader whose association has benefited the most from contact and trade with the human colony. The assassination attempt sets off a confusing and complex set of events: who would dare to attack the paidhi, an important but essentially harmless human who lives under the roof and protection of probably the most powerful atevi?

It’s at this point that we should look at C.J. Cherryh’s writing style, in case you’re not familiar with her works, because Foreigner is one of its finest examples and almost impossible to understand and appreciate without considering it in that light.

Cherryh usually writes in an incredibly tight third person limited perspective. In Foreigner’s case (once the “Prologue” is over) we see everything from the point of view of Bren. Even though the prose is written in the third person and fairly structured, it’s essentially a “stream of consciousness” narration that shows Bren’s thought patterns as they occur and as they are affected by events around him. That has two immediate effects: Bren’s (and so ours) knowledge is limited by his often incomplete understanding of the situation, but, importantly in the context of this series, it also benefits from his unique cultural awareness.

As a result, Bren is both the best and worst possible narrator for this story if, as a neutral observer, you want to understand exactly why the atevi are in such an uproar. Worst because he just doesn’t know what set off the chain of events depicted in this book, until someone bothers to tell him towards the very end. He is clueless when it comes to the main driver of the plot of this novel. Partly because of this, he lacks any sort of agency until late in the book. He has no power to steer the narrative. He is physically weaker than the atevi. He is lost, off the grid, unable to contact any other human. And, to cap it all off, he just has no idea about what happened. (Note: see Ann Leckie’s reaction to this point elsewhere on this site.)

On the other hand, he’s also the best narrator possible for this story, because as paidhi, he has a more complete understanding of atevi psychology and society than any other human (and, obviously, vice versa). He’s devoted his life to understanding the atevi, who may look humanoid (though much taller and stronger) but have a completely alien mindset. Their emotions don’t work the same way. The way they perceive relationships and loyalty is entirely different.

Foreigner is essentially the story of a man who has devoted his life to trying to make sense of an alien culture and who now continues to do so during a pivotal time and under highly stressful circumstances. The crisis between the two cultures that is beginning to brew is mirrored in Bren’s own mind, as his mainly intellectual fascination suddenly turns into a life-or-death situation, forcing him to re-evaluate certain assumptions and habits that allowed him to function but also led to potentially costly misunderstandings.

There are only a few authors who could pull off a book like Foreigner. The level of nuance and detail in Cherryh’s prose is what makes it work, creating a slow, deliberate, multifaceted look at the thought processes of a character who doesn’t have the full picture but is trying to reason his way to it. There are paragraphs, pages even, of Bren trying to process recent events in light of the historical situation on the planet, his personal and professional relationships, and his own observations.

This creates a reading experience that’s the literary equivalent of shaky handheld camera footage accompanied by an internal monologue voice-over: yes, it’s sometimes slow, confusing, and obviously focusing on things that are less than important in the big picture. You’re forced to process raw footage, just like the point of view character. At the same time it makes for a uniquely immersive experience.

Steven Brust recently wrote a blog post entitled “Making the Reader Work”, including a quote from David Wohlreich (@wallrike): “When a fish explains what water is, I’m unhappy.” C.J. Cherryh is the kind of author who should make readers like this happy: in her fiction, not only does the fish rarely explain what water is, but often the reader isn’t even aware that there are such things as fish and water, or that there’s anything but water to consider.

(Interestingly, Cherryh has several works that are even more challenging and uncompromising in this regard: see, for example, the opening volume of her Fortress series, which for the first 100 pages or so borders on the incomprehensible because the author is ruthlessly consistent in limiting herself to the main character’s point of view.)

In Foreigner, Bren is (if you’ll pardon the pun) a fish out of water. The end result is a slow, often confusing but extremely rewarding novel. The limited perspective is sometimes difficult, yes, but it also allows Cherryh to introduce the many other aspects of this novel and series in a piecemeal fashion: culture shock, multiculturalism, colonial and post-colonial relations. The Foreigner series offers a broad socio-political tapestry, from the various factions on the human side to the complex structure and history of the atevi.

Unwrapping that “post-colonial relations” bit somewhat: the humans are in a unique position here, having more or less crash-landed in the middle of a Steam Age level-culture while carrying the knowledge of thousands of years of human science. They allow their advanced knowledge to trickle into atevi culture, constantly trying to balance progress (and profit) with preservation. One of the long term goals is steering the alien culture towards a space program. Some atevi are strongly opposed to any human influence on their society, while others are impatient for more advanced science. Humanity itself has all kinds of factions, including one that feels they shouldn’t have landed on the planet in the first place. There are many sides tugging in different directions, and again, the reader has to figure all of this out based on one character’s perspective.

If the book has one weakness, it’s that there isn’t any kind of resolution. If anything, you end up with more questions than answers. It’s best to consider Foreigner as part one of a three part novel and be ready to get to the next volume in the series. Cherryh does provide some closure at the end of each three book arc (or at least of the two arcs I’ve read so far), but that’s not really the point of this novel and series anyway.

Foreigner is one of the most in-depth, uncompromising examinations of the way cultures interact in science fiction. Rereading it after all this time and with the added benefit of having read some of the later books in the series, I discovered a whole new level of complexity that’s probably almost impossible to appreciate on a first reading—complexity on almost every level, from Bren’s personal life and the subtle interactions of the atevi characters on the micro-level to the incredible socio-political depth on the macro-level.

I’ve been reading mostly new releases for review purposes lately. Rereading Foreigner was a pleasure. I’d forgotten that C.J. Cherryh is simply one of the most unique minds working in SFF right now. I’m actually a bit annoyed that I let myself lose track of this author and series for so long, but fortunately, as I just learned, these books lend themselves to a second reading really well. I’m looking forward to reading through the next five books again and then treating myself to the other eight.

One of my very favorite things about this book is how very alien the atevi are–they really are absolutely unlike humans and it’s really a remarkable accomplishment that they are so consistently alien and that Bren’s desire to have a human connection with them is both natural but also the very worst thing he could possibly do.

I also really love the moment of first contact between the atevi and the humans. Actually, I really loved the two sections that start the book–you get such a vivid sense of the desperation of the crew and why the engineers would demand such privileges in exchange for the risks they took in order to save everyone. I think it’s in this one–it’s definitely in one of the first three books, as those are the only ones I’ve read so far–where it’s implied pretty strongly that the human ship fell, somehow, into another universe. Which is a fascinating idea in and of itself.

When I read this for the first time, I somehow thought that the original colony ship originated from the same fictional universe as her main Alliance/Union series, but upon rereading I couldn’t find that reference. It probably doesn’t matter anyway, but I thought it would be a nice touch.

And yes, Bren’s just a fascinating character, so torn between his rational understanding and his emotional need to just, somehow, connect with them.

Cherryh does alien aliens pretty damned well.

Nice review. You should submit this to SF Mistressworks run by British SF author Ian Sales. SF Mistressworks is a review collating site of book reviews (of pre-2000 works) by female authors.

http://sfmistressworks.wordpress.com/

Thank you, and done!

Interesting. My only experience with her has been the Fortress series – and, as you say, those first 100 were nearly incomprehensible. Despite that, I liked it, and have kept her on the shelf for a future read. From the sounds of it, I may be better off diving into the Foreigner series first, then letting that fish lead me back to her fantasy.

Yeah, Fortress is a hard one to start with. In general, I’ve enjoyed her SF more than her fantasy – she writes aliens like no one else. Foreigner, Alliance/Union, Faded Sun, Chanur — all great places to start.

So glad you’re rereading this and hopefully also reviewing! One of my favorite series. I’ve reread, and now listened to it more than once. (It’s out in audio and I love audiobooks). Great review, Stefan!

Yeah, I plan to write brief reviews of the other books too, when I get to them. Probably not quite as long/in-depth as this one, though!

I’m glad to see your review of this. I need to start the Foreigner series one of these days. I’m a huge Cherryh fan, but she’s so prolific, I can’t keep up.

I didn’t have any problems with the early parts of Fortress in the Eye of Time: a slow burn, definitely, but perfectly comprehensible, and the threads from the beginning are woven together nicely by the end.

Foreigner was far more difficult. A friend I discussed it with made me realize that I hadn’t the faintest idea what was really going on in the book. Admittedly she’d read the whole series to date more than once, and I’d only finished the first one…

Anyhow, hooray for challenging books! Of the two Cherryh novels I mentioned, I’m far more likely to reread Foreigner than Fortress for the simple reason that I know for sure I’ll get more out of Foreigner next time, whereas I’m not sure that would be true of Fortress (as much as I enjoyed it).

Excellent review! I love this book, and its sequels. Though, since you’ve read AJ, you know what a tremendous debt I owe to Nand’ Cherryh and this book in particular.

I do take issue with part of your analysis, though. This bit:

He is clueless when it comes to the main driver of the plot of this novel. Partly because of this, he lacks any sort of agency until late in the book.

This isn’t actually the case. It only looks that way until late in the book.

Spoilers ahead!

So. Bren’s actions are, in fact, pivotal to the outcome of events, pretty much from the start. His choice to fire at the assassin causes a particular reaction among Tabini’s opposition, and part of the result of that is Tabini sending Bren to Sidi-ji. Bren takes it–in a moment of near-despair–as Tabini considering Bren to be a disposable asset, but I see it as Tabini saying to his grandmother, “You think I’m wrong to rely on Bren-paidhi? Try him and see.” Knowing full well what sort of trials Ilisidi will make, and what sort of person Bren is. But of course, Bren might still fail the test.

So from the moment he arrives at Malguri, his every word and action–how he treats the Malguri staff, his giving autographs to the tourists when he doesn’t have to, even walking the retired couple to the door as they tell him about their toddler grandchild, his reaction to being accidentally poisoned by Ilisidi, and finally the night in the cellar–the lives of millions of people hang on all of these things. If Bren had chosen differently, if he’d been dismissive of the servants, of atevi concerns, if he’d turned on Tabini in the cellar to save his own life–everything would have been different. Because in order to do this Bren has to be put in a situation where he has nothing to guide him except his most basic values and loyalties, and where those values and loyalties will be pushed all the way to the wall, it looks like a story where everything is happening to him and he’s doing nothing, but just by holding the line no matter what, he’s influenced events, changed Ilisidi’s mind, and prevented a war between Mospheira and the mainland–a war Mospheira would certainly lose and would likely end in the extermination of all humans on the Earth of the Atevi. And when the situation is revealed, and you look back, you see that nearly every choice he made up to that point–even the seemingly very small ones–was deathly important.

Which means the whole thing pivots on his character–which means the entire novel is pretty much concerned with him, as a character and why it makes perfect sense to focus on that. And boy, does it. It’s being willing to stick with Bren–along with all the fabulous interactions with the other characters and the world, yes–that gets you through Foreigner even when it looks as though he has no agency.

I could also insert here a rant about the way the common (generally decent) advice about characters having agency can obscure the very small, subtle kinds of agency people have, but I’ve got other things to do today.

Ultimately, the very valuable lesson I learned from this book was that if you have a compelling enough character, you’ll follow them freaking anywhere–you’ll wait hundreds of pages for a payoff. The author has to deliver it, of course, but “I am really drawn into this character drinking tea and taking baths and thinking about politics” can be enough to pull a reader through. The weak spot here, of course, is that readers who don’t find Bren appealing will find Foreigner nearly unreadable, but hey, no book is going to appeal to everyone.

Hmm, it may be that I’m thinking about agency in a different way than you here, because to me it seems that what you describe more or less confirms my original idea.

SPOILERS AHEAD

Yes, Bren affects the outcome of events and the actions of other major players, but (again, until “late in the book”, as I said originally) he does so without having any kind of awareness of what actually caused the chaos – the return of the Guild spaceship. He takes a shot at the assassin, not knowing who/what caused the assassin to be sent. He is kind to the staff at Malguri, gives autographs, resists the attempts to strong-arm into a position he doesn’t believe in, all without knowing what’s really going on. Everything he does affects the outcome, but until he sits down with Ilisidi at the window, he has been operating as if blindfolded, moving (mostly) in the right direction but essentially powerless. He’s shepherded along, stuck on the macheita, fed poisonous tea, given excuses when he asks for a power cord for his computer…

So when I said he lacks agency until the end of the book, what I meant is that he is being moved around as a pawn, and his reactions studied, by others who unlike him *are* aware of the situation. Obviously his actions have an effect, and he always acts with the best interest of Banichi and the human colony in mind, but I don’t think we can say he’s an informed decision-maker.

I definitely agree with your last paragraph. The complexity of both the character and the culture(s) depicted here are enough to make this book a classic for me. I can’t wait until I have a little gap in my schedule so I can get to book 2.

Oh, you’re determined to make me rant. 😉

So, I think that’s far too restrictive a definition of agency. Yeah, Bren doesn’t know what the surrounding situation is–but that’s completely separate from his ability to choose, and to act on events.

He does know things are deadly–he just doesn’t know why. But that doesn’t mean his choices aren’t choices, and aren’t active. He’s doing plenty to try to change and control the situation he’s in. He’s not just letting events wash over him–he’s reacting very deliberately, partly according to his best (though of course entirely incomplete) understanding of the situation, but largely according to his own loyalties, as I said.

To demand that in order to have agency an actor must have complete knowledge basically means no one alive has agency–except, perhaps, a precious few very powerful and informed individuals. It also means that characters who have very little overt physical or political power are basically excluded from the pool of “acceptable” main characters–they don’t get to have “proper” stories because they don’t have this restrictive version of agency and can only be the center of “victim” stories where everything happens to them, they don’t make anything happen. But in reality, that’s not actually the case. In reality, we all act with incomplete knowledge, we all strive for various things, try to make things happen, and sometimes succeed and sometimes fail–but demanding this extra bit to agency erases the agency that most people actually have.

And it’s funny how often that version of agency excludes, say, women from being the centers of stories.

Bren is being moved around the board, yes–but he’s also completely changing the game, affecting what moves the others on the board are making, not through being manipulated, but by making his own, very consequential choices. He is driving the plot just as much as Phoenix overhead is, just as much as Tabnin or Ilisidi. His not knowing about Phoenix is a whole other issue that has nothing to do with the question of Bren’s agency.

Okay. I think we mainly have a semantics issue here. Still, I respectfully point out that your third paragraph takes my argument way out there to a place I didn’t intend. First of all, I didn’t say I require “complete knowledge” for agency. I argued from the opposite end, which is the main character’s complete *ignorance* of the main driver of the plot.

If Bren had had even an inkling of what caused Banichi to do what he did before the start of the main story, or what motivated Ilisidi and her association, this would have been a different story. Yes, Bren is changing the game and affecting the outcome, but he’s doing so blindly, unaware of what started the game in the first place, until the very end. He’s reacting to changes in his immediate environment and circumstances without knowing what caused those changes.

So, maybe my understanding of agency is different from yours. Maybe it’s flawed. I don’t know. But please note that the words you put in quotes (proper, victim, acceptable) are nowhere near my original argument, and especially the part of excluding women from the center of stories. That’s not what I was trying to say or even imply here. I also (obviously) don’t think lack of agency is necessarily a bad thing or would in any way invalidate the character or the novel. I also didn’t mention it in a negative way in the review. To me it’s actually a key to what makes this novel so great – the contrast between Bren’s unique cultural awareness and his lack of information about what’s going on creates a unique sort of tension.

I have read all of the series. It was wonderful to get a view about the first book as it has been so long since I read it and Bren has grown so much in the series. Thanks for the reminder.

My pleasure, and thanks for commenting! I’ve only read the first 6 books, but I’m hoping to read and review all of them in the course of the next 12 months or so.

This book is one that’s been on my mental back burn to try for years, but I’ve tapped out early on two books by Cherryh (The Dreaming Tree and Downbelow Station) so I’m hesitant to dive right into this one. How does Foreigner compare to those two, if you’ve read them?

Those books felt very different than any other Cherryh I’ve read…even the Fortress series.

The Dreaming Tree is challenging. I had trouble with it too, originally. Downbelow Station is the one people always recommend starting with, but it didn’t blow me away like some other entries in the Alliance/Union/Merchanter universe. It doesn’t help that it starts with a huge info-dump. I think it works better if you’ve read the 2 that take place before it (Heavy Time and Hellburner). Anyway, to your question, I think Foreigner stacks up favorably against those two. You might also try Chanur, which is some of the most fun and accessible SF she’s written.

I think I’ll give her the proverbial chance of the third strike. I gave up on DOWNBELOW at about the half-way point, story felt like it was going nowhere.

Pingback: Guest Post by Ann Leckie: Skiing Downhill, or Agency in C.J. Cherryh’s Foreigner | Far Beyond Reality

Pingback: Linkspam, 11/15/13 Edition — Radish Reviews

Pingback: Invader and Inheritor by C.J. Cherryh | Far Beyond Reality

Pingback: Foreigner, CJ Cherryh | SF Mistressworks

Pingback: Speculative Fiction 2013 (Ana Grilo and Thea James, Eds.) | Far Beyond Reality

Pingback: Mind Meld: You Know We’re All About That Backlist | Far Beyond Reality

Pingback: Mini-review: Protector (Foreigner #14) by C.J. Cherryh | Far Beyond Reality